Ottokar IV

Ottokar IV, king of Syldavia (1360)

Quarterly; Or, a pelican displayed Sable;

Gules, two increscent moons Argent, fesswise.

Crest: A royal crown Or lined Gules, over a closed helmet Or,

between the Scepter of Ottokar in bend and

a scepter of justice in bend sinister,

both Or, with staffs in saltire extending below the shield.

Mantling: Or and Azure.

Motto: Eih bennek, eih blavek.

(Here I am, here I stay.)

That motto appears below the shield, on a curling ribbon

bearing

the insignia of the Golden Pelican Order.

A Centennial Tribute to Hergé

©

2007 by Gérard P. Michon, Ph.D.

| |

|

Modern album cover

(after 1947).

|

Hergé was the nom de plume of the late Belgian cartoonist

Georges Rémi

(1907-1983) who is best known as the creator of the 24 adventures of

Tintin (Tin-tin) and his dog Milou (Snowy).

Hergé's lesser known series include Quick & Flupke

(12 titles), Jo, Zette & Jocko (5 titles) and

Popol & Virginie.

The famous pseudonym comes from the French pronounciation of Rémi's initials,

following the common Belgian custom of listing someone's surname first:

REMI, Georges (RG = Hergé).

Hergé was born in Brussels one hundred years ago, on May 22, 1907.

From Syldavia to the Moon

Hergé created the fictitious kingdom of

Syldavia as the backdrop for the 8th

adventure of Tintin : Le sceptre d'Ottokar

(King

Ottokar's Sceptre). This was

originally published as a serialized comic strip in 1938 and 1939,

under the title "Tintin en Syldavie" in

Le Petit Vingtième

(which was the weekly youth supplement, from 1928 to 1940, of the

Vingtième Siècle, the newspaper

from Brussels where Hergé started working in 1925).

Syldavia is presented (page 7) as a Balkan state located next to the rival country

of Borduria.

The intrigue is based on the identification of

Syldavian royal power with Ottokar's Scepter :

Should a reigning monarch lose that scepter, he would have to

abdicate in shame, thereby leaving political power up for grabs...

Incidentally, this story features the first appearance (page 28) of

one of Hergé's best-known characters,

the opera singer Bianca Castafiore, as she gives Tintin a car ride,

on her way to a concert at the Kursaal

of Klow, capital city of Syldavia.

Royalist Syldavia and "Moustachist" Borduria

would resurface in the 1956 story L'affaire Tournesol,

where Bianca Castafiore performs at

the opera house of Szohôd, capital city of Borduria.

Finally, of course, Bianca Castafiore

("Le Rossignol Milanais") ended up with the

title role in Hergé's twenty-first Tintin adventure

(Les bijoux de la Castafiore, 1963) where a newsreport

(page 48) mentions the twenty-first

congress of the "Moustachist Party" at Szohôd...

| |

|

Page 38: Jacobs & Hergé.

|

The status of Syldavia as a Balkan state was visually reinforced in 1947,

when part of the Ottokar

album was redrawn (for its first color edition)

by Hergé's collaborator

Edgar P. Jacobs

(1904-1987) of Blake & Mortimer fame.

The moniker Ottokar may conjure up the word "autocar"

(which denotes a long-distance bus in French)

but it's also the actual name of several historical figures,

including Ottokar I,

duke and king of Bohemia (1198-1230) mentioned in the encyclopedia article read

by Tintin on page 7 of King Ottokar's Sceptre...

The fancy Syldavian language, used by Hergé in the above motto,

is simply a slavic-looking spelling of the real-life Marollien

slang, as spoken in a popular quarter of Brussels

(that undocumented piece of humor seems lost on most readers,

including Belgian ones).

| |

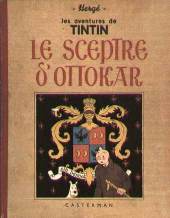

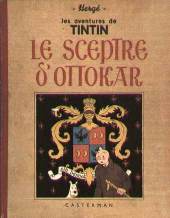

Original (1939) album cover.

|

The above coat-of-arms of Syldavian kings may sport an "authentic" look,

but seasoned heraldists will notice several unusual things about it

(besides the pelican charge which is heralded

as the national symbol of the fictitous kingdom).

In particular, one of the mantling's tinctures (Azure)

does not occur in the shield and

heraldic crescents oriented this way are very rare.

Hergé took no chances of any "coincidental resemblance" with an

actual coat of arms.

Actually, the original design was just black-and-white.

The above color version is from the title page of modern editions

(after 1947).

The cover of the 1939 black-and-white album (at left) featured

that coat-of-arms with single-color mantling, dubious shield tinctures

and no scepters in saltire.

Pierre Assouline (1996) reports that Hergé wanted gold printing

for the coat-of-arms and the scepter on that particular drawing.

The editor vetoed that costly idea and suggested brown hair for Tintin,

for better contrast against a plain yellow field in the shield.

Hergé insisted that fair hair was

part of Tintin's identity (Tintin's hair became darker with

later color albums).

Ultimately, the contrast issue was resolved by printing the relevant field(s)

in blue ("Azure") in spite of the resulting ugly balance.

Better heraldic tinctures were retained for the color

editions of Ottokar, as the coat-of-arms was taken off the cover

and away from misguided bickering.

The Azure mantling which remains may be due to that anecdote about

the 1939 cover (normally, a two-color mantling features two

tinctures, a metal and another color, which are both

present prominently in the shield).

Syldavia would be the country from which Tintin would depart for the Moon,

in his adventures #16 and #17:

Objectif Lune (1953) and

On a marché sur la Lune (1954).

Hergé and Jules Verne (1828-1905)

The work of Hergé reflects the popular fascination for Science and

Exploration in the

nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth century

(before consumerist technology kicked in).

The influence of Jules Verne, the father of science fiction,

was instrumental in this fascination and Hergé found inspiration

in Verne's work (although Hergé always denied it).

The adventures of Tintin do feature a quintessential absent-minded

professor: Tryphon Tournesol (called

Cuthbert Calculus in the English translation).

Tournesol first appeared in Le trésor de Rackham le rouge

(Red Rackham's Treasure) as the inventor of a shark-shaped

submarine.

(He quickly invested the proceeds of that invention to help buy

Moulinsart, the ancestral castle of Captain Haddock

which would later serve as a home base for Tintin, Haddock and himself.)

By Hergé's own account, the Tournesol

character was modeled after

Auguste Piccard

(1884-1962) of the University

of Brussels (pictured at left) except for the diminutive stature

of Tournesol! (Piccard was a tall man.)

The adventures of Tintin do feature a quintessential absent-minded

professor: Tryphon Tournesol (called

Cuthbert Calculus in the English translation).

Tournesol first appeared in Le trésor de Rackham le rouge

(Red Rackham's Treasure) as the inventor of a shark-shaped

submarine.

(He quickly invested the proceeds of that invention to help buy

Moulinsart, the ancestral castle of Captain Haddock

which would later serve as a home base for Tintin, Haddock and himself.)

By Hergé's own account, the Tournesol

character was modeled after

Auguste Piccard

(1884-1962) of the University

of Brussels (pictured at left) except for the diminutive stature

of Tournesol! (Piccard was a tall man.)

Such benevolent characters were typical of comic strips of that period

(probably more so than later "evil scientists").

One prominent example is the Savant Cosinus character,

whose very name became a French locution.

Savant Cosinus was inspired by

Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) who was a

caricatural real-life incarnation of a true universal genius

surprisingly inept at some common tasks.

Like Jules Verne before him, Hergé was criticized for scientific inaccuracies.

Sometimes wrongly so.

Some misguided commentators have ridiculed Hergé for showing slow-burning

match fuse being used to ignite dynamite in outer space. They argued that the thing would not

burn without air... Yes it would! Match fuse contains an

oxidizer that allows it to burn underwater!